When visiting this year’s Smart Country Convention in Berlin, one gets the impression that cities and municipalities globally are more or less on the verge of becoming “smart”. But is that truly the case? We found some lighthouse examples and one of the biggest obstacles on the way to a smart future.

As we support the public sector, we participated in the Smart Country Convention Berlin last week. This forum for the exchange of strategic advice provided the opportunity to learn more from experts about the current state of affairs. While most cities are facing unique situations on a granular level, many places struggle with similar challenges. This year’s partnering country – and role model – was Lithuania. For them, becoming smart was the most pragmatic choice: “We’re not big, we’re not rich, so we have to be smarter”, their Foreign Minister Linas Antanas Linkevičius explained.

The impressive Baltic state has been so successful in fact, that its capital city Vilnius is overwhelmed by the incoming UK tech companies looking for new places to run their business. The city’s recipe for success consists of both top-down and bottom-up approaches. By creating the optimal legal frameworks and infrastructure conditions, the government paves the way for young companies to thrive with new business models.

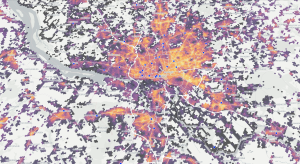

Vilnius: The Impact of a Radical Open Data Policy

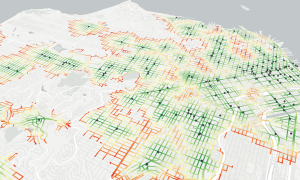

Some of these companies are working towards new transport solutions, with good reason: “Regardless of size, all cities have mobility issues”, the mayor of Vilnius, Remigijus Šimašius said on stage. Once citizens establish routines, adjustments are difficult because of inherent resistance to changing habits (individual car ownership for example).

The mayor reminded us that the main beneficiaries of mobility are neither the municipalities nor the service providers, but the people. Mobility should not be an end in itself. Instead, mobility solutions should focus on the benefits they bring to their users.

The starting point of innovations should be micro-decisions of citizens as opposed to some overarching goal. But how to tackle all these challenges? One way, Vilnius decided, was a radical open data policy. Vilnius claims to be one of the first in Europe to create a public city data platform that provides open-source data for all businesses and citizens – “without excuses”. As a consequence, since September 2017 it’s the home of Trafi, one of the most advanced mobility apps in the world. Trafi bundles all public mobility solutions, making it easy to navigate the city without a private car. This is not a one-way success story tough. Trafi provides the city administration with so much new data that it’s fundamentally changing traffic planning.

Low Quality and Bad Coverage May Render Open Data Unusable

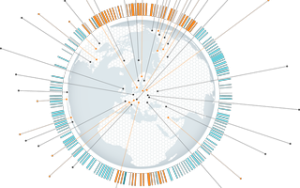

But if igniting the spark is so easy, why are many city governments struggling to follow that open data approach? In our daily work with open data sources from all over the world, we encounter a wide range of problems. Two of the most significant ones: Coverage and quality.

For many of our customers, precise travel time analysis with public transport is key for answering their mobility questions. Integrating public transport data for Germany alone means using data sets from more than 80 federal transport authorities, many of which have to be contacted personally and may be reluctant to share their data. Consequently, it’s almost impossible to create a complete picture of Germany’s public transport landscape at this moment.

On the other hand, good intentions on their own aren’t enough, the correct execution is equally important. Large-scale data sets need homogeneous structures. Lina Bruns, a research assistant at Fraunhofer FOKUS, demonstrated at the Smart Country Convention how minor syntactical inconsistencies in data descriptions – such as putting a phone number as either 040/9595 or 040-9595 – can cause considerable additional effort, while incomplete data sets can quickly render all available information unusable for the majority of analytical purposes.

Bruns argued that agencies lack strategy, processes, tools, or resources to make sure their data solutions fulfill the necessary quality requirements. To help them, FOKUS released new guidelines this week for the improvement of data and meta-data quality, focusing especially on the necessary setup and structure of data.

While this is certainly a great help for those who already have an open data strategy, we hope that events like the Smart Country Convention convince more government agencies that they need one in the first place.